The information provided below is also available at the NOVA’s Guide to Intellectual Property and Knowledge Transfer

A. Knowledge & Technology Transfer Overview

What is Knowledge Transfer?

Knowledge Transfer (KT) is a process that allows research results, discoveries, scientific findings, technology, data, software, literary works, know-how and other forms of intellectual property (IP) to flow between different stakeholders. From a University perspective, it refers to the transfer of such assets to industry, governmental institutions or society at large, therefore enhancing competitiveness, development and welfare, through the generation of social and economic value.

Knowledge transfer occurs via both formal and informal channels. Formal channels typically involve a legal arrangement through which the parties clearly establish the terms of the transfer of given intellectual assets (e.g. licensing, contract-research and other forms of research commercialization). Informal channels, on the other hand, refer to personal contacts and hence to the tacit dimension of knowledge transfer. Examples include human capital mobility, teaching, mentoring, interactions in conferences and seminars, informal exchanges between researchers or academia and industry, or students entering the workforce.

What is Technology Transfer?

Technology Transfer (TT) is the process by which new inventions and other innovations stemming from scientific and technological research are turned into marketable products and services.

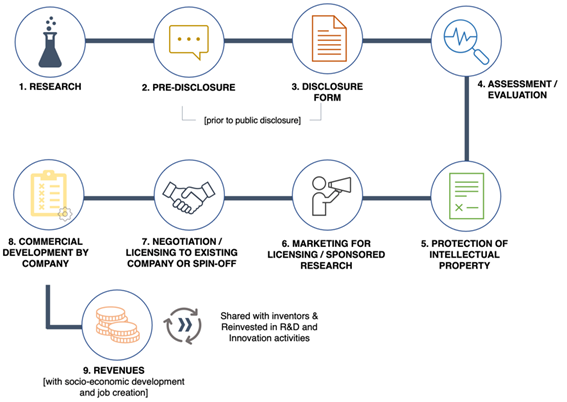

For the purposes of this guide, TT refers to the commercialization of research results, which typically begins with the discovery of novel technologies, followed by the disclosure, evaluation, and protection of these technologies. Traditionally, next steps include marketing, potential licensing agreements and the development of products or services based on the technical inventions, although these steps can vary in sequence and often occur simultaneously. The financial returns resulting from this process can then be used for further research and innovation activities. Technology development can occur through the “market pull” approach, which attempts to provide products to the market demands; or via “technology push”, when R&D in new technology drives the development of new products.

“Technology Transfer refers to the commercialization of research results, which typically begins with the discovery of novel technologies, followed by the disclosure, evaluation, and protection of these technologies”.

What are the typical steps in the Knowledge Transfer process?

The knowledge transfer process can be summarized in 9 steps. Please note that (i) these steps can vary in sequence and often occur simultaneously, and (ii) this particular flow is essentially focused on research commercialization, although there are other forms knowledge transfer and valorization – not necessarily linked to direct revenue streams or channeled through more informal relations – that are also an important part of our mission, namely research communication, education or staff expertise that can positively impact the life of citizens and improve society; and (iii) that this process may take months or even years to complete. For inventions, the amount of time depends on several factors such as the Technology Readiness Level (TRL), potential markets, competing technologies, additional work needed to bring the technology to the market, available resources, or the willingness of the inventors.

- Research. Observations and experiments during research activities often lead to discoveries, inventions or other research outputs (e.g., software, research materials) with potential commercial value. Often, multiple researchers may have contributed to a certain IPR.

- Pre-Disclosure. An early contact with NOVA Impact (or IRIS if you are related to FCT NOVA, or the Innovation Unit if you are related to ITQB) to discuss your idea and to provide guidance with respect to the disclosure, evaluation, and protection processes described below.

- Disclosure Form. Formal report of the invention or Copyrightable material to NOVA specialized services – the written notice that begins the formal transfer process. The Invention or Copyright Disclosure Form remains a confidential document and should fully document your invention so that the options for commercialization can be evaluated and pursued.

- Assessment / Evaluation. The period in which the Disclosure Form is reviewed (with your input), prior art searches are conducted, in addition to market analysis to determine the commercialization potential of the disclosed research outputs. The evaluation process will guide the best strategy to commercially explore the disclosed results, that may pass to sell or licensing to an existing company, creating a new business start-up or social enterprise or, if applicable, collaborating with industrial partners to increase the TRL prior to commercialization.

- Protection of Intellectual Property. The process in which the best protection route is defined to maximize the social and economic impact of the research outputs. In case of patent protections, the process typically starts with the filing of a patent application within INPI and, when appropriate, international applications. Protection and maintenance fees may require thousands of euros, particularly if the inventions are protected internationally. Other protection options include Copyright, trademark, design or trade secret, for example. At NOVA, this process is conducted with the help of patent attorneys or other external IP experts.

- Marketing. Although this process is conducted by the University, the active involvement of inventors/authors can dramatically enhance its success. This process relates to the sourcing of potential licensees and/or candidate companies with expertise, resources and business to bring the work or technology to the market, which includes its showcase in national and international platforms or events. Marketing efforts can also focus on finding industry sponsors to fund additional research or proof-of-concept studies. If the creation of a new business spin-off presents as the optimal valorization route, NOVA will work, within its capabilities, to assist the founders in the venture creation and application to the NOVA Spin-off seal.

- Negotiation / Licensing. After a negotiation process to define the terms and conditions for the commercialization of the IP asset, a license agreement is made between NOVA and a third party, in which NOVA’s rights to a technology or Copyrighted material are licensed for financial and other benefits. This applies both to new spin-offs and established companies. NOVA Spin-offs formally recognized as such can obtain an exclusive license of an IP right developed by its promoters, free of charge until the commercialization stage.

- Commercial Development. The licensee company continues the advancement of the licensed IP and makes other business investments to develop the product or service. This step may entail further development, regulatory approvals, sales and marketing, support, training, and other activities.

- Revenues. Revenues received by NOVA from licensees are distributed to inventors/authors, to Organics Units, and to Research Units or research groups to support new R&D and innovation activities. The development and commercialization of innovative solutions has the ultimate goal of giving back to society, by contributing to the economic development and social welfare of the country, and to the creation of highly qualified jobs.

B. Intelectual Property in a Nutshell

This section includes a description of concepts related to Intellectual Property, focusing on the main instruments of Intellectual Property Protection, from inventions and industrial designs to distinctive trade signs, trade secrets or artistic and literary works, including software.

B1. Intellectual Property Rights – General Considerations

What is Intellectual Property (IP)?

Intellectual property (IP) refers to creations of the human mind that benefit from the legal protection of a property right, being essentially intangible assets. The main legal mechanisms for protecting IP are patents, trademarks and Copyright, covering a variety of creations, from literary and artistic works, symbols, names and images, to inventions and trade secrets.

Intellectual property includes all exclusive rights to intellectual creations. It encompasses two types of rights:

- Industrial Property, which includes inventions (patents or utility models) and topography of semiconductor products, protecting technical creations, as well as industrial designs and models, trademarks, logos, and geographical indications, protecting mainly aesthetic creations and commercial signs; and

- Copyright and Neighbouring Rights (“Direitos de Autor e Direitos Conexos” in Portuguese), intended to protect literary and artistic works – such as books, music, films, photographs or computer programs. Copyright protects both economic rights, that allow right owners to derive financial reward from the use of their works by others, and moral rights, that allow authors and creators to take certain actions to preserve and protect their link with their work. Related rights are typically related to rights that have granted to three categories of beneficiaries: performers, producers of sound recordings (phonograms) and broadcasting organizations.

The importance of trade secrets (“segredos comerciais”) is also recognized in the Portuguese Industrial Property Code, to protect confidential information with commercial value, whose obtaining without the consent of the trade secret holder constitutes an illegal act. Learn more about trade secrets in Europe here.

See http://www.wipo.int/about-ip/en for a general introduction to IP.

“Intellectual property includes all exclusive rights to intellectual creations, encompassing two types of rights: Industrial Property and Copyright & Related Rights”

What is the difference between Intellectual Property and Intellectual Property Rights?

While Intellectual Property (IP) refers to creations of the human mind, including all forms of knowledge that we are able to create, such as inventions, literary and artistic works, symbols, names, images, and designs used in commerce, Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) are the legal titles to which we apply for to get the right of preventing others of using and exploring IP.

In a broader sense, IP can thus be considered the knowledge that we create every time we perform research activities. In turn, IPR are the legal titles that ascertain the ownership of such knowledge, the contract that is made between the applicant and society in order to value the investment made by the IP owners in its development. Both IP and IPR can be exchanged between organizations leading to improved use of said knowledge and to innovation. IPR are the tools by which such transaction of IP is more valued since it offers a competitive advantage to the entities that have the authorization to use and explore it. By transferring just IP we are not able to prevent others from using it without our authorization. IPR allows us to prove that we own a certain IP asset and others can only use it if we allow it and under agreed conditions.

Are intellectual property and industrial property the same concept?

Not exactly. Intellectual property covers all exclusive rights to intellectual creations, including industrial property and Copyright. Industrial property is therefore a subset of intellectual property which take a range of forms, including patents for inventions, trademarks, industrial designs and models, and geographical indications.

What are the different instruments of Intellectual Property protection?

- Inventions: patents or utility models;

- Distinctive trade signs: trademarks, logos, geographical indication or designation of origin;

- Design: industrial designs;

- Artistic and Literary Works (including software): Copyright

- Trade secret

Does IP protection have a time limit?

Intellectual Property is protected only for a limited period of time, beyond which it is no longer protected and falls into the public domain. In general, when an IP right expires, everyone may use it with no restrictions from the right holder.

The term of protection shall be no less than 20 years for patents. The term of protection for utility models is shorter than for patents and varies from country to country (usually between 6 and 15 years). In Portugal, utility models have a maximum duration of 10 years. The term of protection is counted from the date of filing an application, and not from the granting date.

In turn, trademarks and logos protection lasts for 10 years, and it can be renewed indefinitely for equal periods, while design registration can be maintained for 25 years (registration at INPI is valid for 5 years and may be renewed for another four periods of 5 years)

In Europe and Portugal, in particular, Copyright protection generally lasts for 70 years after the death of the author, but the term of protection for Copyright can vary from country to country.

“The term of protection shall be no less than 20 years for patents, 10 years for utility models, trademarks and logos, and 5 years (up to 25) for industrial designs”

What is the difference between “Background IP” and “Foreground IP”?

These terms are often used in Consortium agreements that establish research partnerships funded by public national and international Agencies.

Background IP, as defined by the European Commission, means any data, know-how or information – whatever its form or nature (tangible or intangible), including any rights such as intellectual property rights – that: (a) is held by the beneficiaries before they acceded to the Agreement, and (b) is needed to implement the action or exploit the results. Therefore, Background IP includes all Intellectual Property, independently of being protected by IPR or not, that a partner brings to a project and will be used as the foundation of a Result.

Foreground IP, or Results, as defined by the European Commission, is any (tangible or intangible) output of the action such as data, knowledge, or information – whatever its form or nature, whether it can be protected or not – that is generated in the action, as well as any rights attached to it, including intellectual property rights.

It is very important to define the Access Rights to Background and Foreground IP at the beginning of a research collaboration with a third party, i.e. the rights to use results or background under the terms and conditions laid down in the research agreement.

While, as a rule of thumb, these Access Rights, either for Background and Results are granted royalty-free for the implementation of the project, the use of Background and Results, either protected or not, by a Partner must be regulated by appropriate separate contractual mechanisms, following NOVA’s IP Policy.

Also important is to appropriately manage Access Rights: one has to be careful not to grant the same Access Rights to different partners, for example, you cannot grant exclusive worldwide licenses to two different partners, as the licenses could not be exclusive.

What is an invention?

An invention is a product or process providing a novel and inventive solution to a technical problem. Products include goods and tools, equipment such as production facilities and machinery, and materials such as chemical substances or textiles, while processes describe activities for specific purposes, such as manufacturing processes (work or productions steps for a manufacturing process), control procedures (process steps for using an apparatus or machine) and measuring methods.

We generally refer to as invention, intellectual property which can be protected by patent (but it can also be a utility model). An invention generally consists of several technical features, including relations between them. In short, an invention uses technology to solve a specific problem in a new, non-obvious and technical way. The technical character necessary for patenting requires that the laws of nature are used to achieve the objective.

Some examples of inventions developed by NOVA researchers can be found here.

“Inventor” vs. “Author”: what do you need to know?

These terms are often confused, and it is important to know the distinction to appropriately manage Intellectual Property.

Inventors are those responsible for creating an invention, and the term inventorship belongs to the intellectual property branch of Industrial Property. On the other hand, an Author is someone that created a piece of writing or other literary work, and as such authorship belongs to the Copyright branch of Intellectual Property. Not all inventors are authors and vice versa.

To determine authorship you select every natural person that contributed to the scientific publication either by writing it or reviewing it. To determine Inventorship there are two main requirements: (i) the conception of the idea and (ii) the reduction of the idea into practice. An inventor to be considered as such must have had an “active contribution” to produce the invention, in the sense that without its personal involvement the invention would not have been devised. On the other hand, a person is not considered an inventor if they only carried out work under the direction of others. For example, project managers or supervisors, or reviewers of text cannot be considered inventors if they did not make any inventive contribution.

An inventor conceives the idea, materially contributes to the development of the invention, provides solutions to problems and implements the innovation. A person that puts forward hypothesis, passively follows instructions, performs routine tasks and executes results testing, is not considered an inventor.

An Inventor is someone who had actively and intellectually contributed to produce an invention;

An Author is someone that created a piece of writing or other literary/artistic work.

How do I know if I have invented or created something?

The concepts of invention and creation can be found in the Portuguese Industrial Property Code. Inventor refers to those who produce objects susceptible to protection by patent or utility model, while a creator refers to those who produce objects susceptible to protection by topography of semiconductor products or designs.

The following activities are not regarded as inventions:

- Discoveries (e.g. when a gene is merely found and described), mathematical methods and scientific theories;

- Naturally occurring materials and substances (in its natural state);

- Aesthetic creations;

- Projects, principles and methods of intellectual activities related to gaming or business activities;

- Software, as such, without any technical application;

- Presentations of information.

Author refers to literary and artistic works whose concepts can be found in the Portuguese Copyright and Related Rights Code.

B2. Patents and Utility Models

What is a patent?

A patent is a time-limited and territorial IPR which provides the patent owner(s) exclusive rights on the patented technical invention. It allows the owner to prevent others from using the invention for commercial purposes for a period of 20 years. Patents can be used to protect products, processes, or use of a product that provide a new way of doing something, or that offers a new technical solution to a problem.

Patents are sometimes considered as a social contract between the applicant and society, that grants protection to innovators (thereby also increasing the motivation to innovate) in exchange for disclosure of the invention to the society at large.

A patent should describe the technical problem to be solved, how the invention solves it, and how this offered solution differs from the known prior art.

The patent owner may give permission to, or license, other parties to use the invention on mutually agreed terms. The owner may also sell the right to the invention to someone else, who will then become the new owner of the patent. Once a patent expires, the protection ends, and an invention enters the public domain; that is, anyone can exploit the invention without infringing the patent (e.g. generic drugs).

However, even if a patent is granted, it is not always guaranteed that the patent owner can use or commercially exploit a patent, since access to other patented inventions may be necessary for such use or exploitation in order to avoid infringement of other IP rights (Freedom to Operate).

What is a utility model?

Similar to patents, utility models protect new technical inventions through granting a limited exclusive right to prevent others from commercially exploiting the protected inventions without consents of the right holders (often 6 to 10 years from the filling date – 10 years in Portugal). They are sometimes referred to as “short-term patents” or “utility innovations”.

In general, utility models are considered particularly suited for protecting inventions that make small improvements to, and adaptations of, existing products or that have a short commercial life. Utility model systems are often used by local inventors.

In practice, protection for utility models is often sought for innovations of a rather incremental character which may not meet the patentability criteria, as the requirements for acquiring utility models are typically less stringent than for patents.

What makes an invention patentable?

An invention can be protected by patent if it meets the three following requirements:

- The invention is new, i.e., it must show an element of novelty, some new characteristic which must not form part of the “prior art”. Prior art means all existing knowledge that has been made publicly available anywhere in the world prior to applying for a patent, including printed and online publications, as well as public lectures and exhibitions. Anything you disclose about your invention before applying for a patent is considered prior art (e.g. a paper, an oral presentation, a LinkedIn post, etc.). Therefore, make sure you keep your invention a secret until it is protected.

- The invention involves an inventive step, meaning that the invention must not be obvious to a person “skilled in the art”, considered to be a hypothetical person who knows the “prior art” in his technical field. If showing the purpose of your invention to the person skilled in the art, this person readily comes up with the same solution, then your solution is not considered inventive.

- The invention is industrially applicable, i.e., the invention must be industrially applicable and practicable (it can be used or manufactured in industry or agriculture), and it must be possible to replicate its implementation.

Also, its subject matter must be accepted as “patentable” under law. Under the European law, for example, mathematical models, computer programs per se, scientific theories, aesthetic creations, plant varieties, discover of natural substances already existing in nature, business methods or methods for medical treatment (as opposed to medical products) are not considered patentable.

Full set of FAQ on Patents at: https://www.wipo.int/patents/en/faq_patents.html

In order for your invention to be patentable, it must be new, inventive and industrially applicable.

Can ideas be patented or protected?

The short answer is no. It is true that ideas are a critical and valuable piece to the overall innovation equation, as nothing can or will happen without an idea. In and of themselves, however, ideas are not monetarily valuable. Without some identifiable manifestation of the idea there can be no intellectual property protection obtained and no exclusive rights will flow. What inventors need to do is identify a problem, formulate the idea and then work toward finding a technical solution. The goal is always to get to the point where the idea it is concrete enough to be more than what the law would call a mere idea, because the moral of the story is that mere ideas cannot be protected, so it is advisable to think in terms of an invention.

What are the three main routes to patent protection?

It is possible to apply to patent an invention in one or several countries individually or by choosing a centralized application procedure such as the European or international procedure (PCT). The procedures can also be combined. The filing date of the first application always establishes the priority date. You can check an example of procedure implemented at NOVA on section E2.

- National patent application

It is possible to apply to patent an invention nationally, i.e. in one country or in several countries individually. An application for a Portuguese patent should be submitted at INPI – National Institute of Industrial Property, where the official language of proceedings is Portuguese. However, the application may initially be filed in English, being that a Portuguese translation thereof must be submitted within one month of the corresponding notification from the Office.

To apply for a patent in Portugal the following elements are needed: i) claims of what is considered new and inventive and characterizes the invention; ii) a detailed description of the object of the invention; iii) drawings necessary for the perfect understanding of the description (when applicable); iv) summary of the invention; v) drawings for publication in the Industrial Property Bulletin (if there are drawings that are necessary to understand the abstract); vi) a title for the invention; and vii) identification data of the inventor(s) and applicant(s).

Average time from filing up to grant of a patent application in Portugal is 2-3 years.

A provisional patent application (PPA) can also be submitted to secure a priority date, without the need to meet all the rigorous requirements of a definitive (non-provisional) patent application. Note that a PPA must be converted into a definitive application within 12 months of filing. Learn more at the INPI website.

- International patent application

With a PCT application, it is possible to request protection in as many member states of the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) – and therefore almost worldwide – as desired. It is a centralized application and search procedure (single language and a single publication). The application is submitted to WIPO, but it can also be done through INPI or the European Patent Office (EPO). The WIPO carries out a search on the state of the art (also known as prior art) and publishes the search report together with the application. Within 30 months after the priority date, it is necessary to initiate the national phase and make requests for examination at the offices desired. The application will be studied according to the national laws of each country, and the granting or refusal are responsibility of that country, which means that the same invention may be refused in one country and granted in another country.

Following the PCT route we have, in most cases, up to an additional 18 months from the time we file an international patent application (or usually 30 months from the filing date of the initial patent application of which you claim priority) before we have to begin the national phase procedures with individual patent Offices and to fulfil the national requirements.

An overview of the PCT contracting states can be found on the WIPO website. Learn more about the PCT application at the INPI website or at WIPO.

- European patent application

With a European patent application, it is possible to obtain patent protection in as many member countries of the European Patent Convention (EPC) as desired. Portugal belongs to the EPC as a member state of the European Union.

The examination of the application – including for novelty and inventive step – and the granting of the patent take place centrally through the European Patent Office (EPO). The European patent grant procedure takes about 3 to 5 years from the date an application is filed. Following the grant of the patent, it is necessary to pay renewal fees in those countries in which one want to keep the patent in force. At the time of the validation of the European patent in the designated countries, national fees are due according to the scale in force in those countries. To request the validation of the patent in a particular country, it is necessary to present the translation of the document into the official language of that country in the corresponding institute (e.g. at INPI, in Portugal).

With the direct European route, the entire procedure is governed by the EPC alone. With the Euro-PCT route, the first phase of the grant procedure (the international phase) is subject to the PCT, while the regional phase before the EPO as designated or elected Office is governed primarily by the EPC.

If a priority of a prior national application is not claimed, the European patent application must be filed at INPI, otherwise the patent, once granted, may not be effective in the national territory. Learn more at the INPI website or at the EPO website.

What is a provisional patent application?

A provisional patent application (PPA) is a patent application that can be used by applicants to secure a priority date of an invention, without the need to meet all the rigorous requirements of a definitive (non-provisional) patent application. A PPA must be converted into a definitive application within 12 months of filing.

The PPA has no practical effect if it is too simplified, vague or comprehensive. The submitted document must show all the technical characteristics that will be later claimed in the definitive application, meaning that new subject-matter eventually found during the twelve-month period cannot be added when converting the PPA to a definitive application, since substantial modifications may lead to a change in the priority date of some claims.

For a year, the applicants can determine whether the invention is commercially viable, decide on a territorial extension and find companies interested in exploiting the technology (although market players are often more confident with definitive patent applications).

A PPA can be a valuable tool to be used in certain, not always, circumstances. Each case should be analysed separately in order to define the best route for protection and commercialization of a particular invention. In other words, a PPA should be wisely used, not as standard but to be applied whenever duly justified and proven to be the most suitable tool for that particular situation.

All top research institutions should be able to simultaneously manage their scientific publications and IP rights with socio-economic potential. Therefore, the need to submit a paper for publication or defending a Ph.D. thesis, for example, should not represent an exceptional situation to file a PPA. Our goal is to create the conditions to always choose the best path for the inventions produced at NOVA, while fulfilling NOVA’s obligations as an institution committed to excellence in education and research (see section B).

What is considered a public disclosure of an invention?

Any communication of an invention to the public is considered a public disclosure. The disclosure can happen in writing, orally or even just by exhibiting the invention to the public (e.g. at a fair trade). As long as the recipient of the information is not bound by confidentiality, the communication is considered to be public.

All public disclosures before the date of filing of a patent application are considered to be part of the prior art. Therefore, technical journals, poster sessions, slides, lectures, seminars, MSc. or Ph.D. defenses (which are public according to the Portuguese law), letters, or even conversations can count as an obstacle to patentability.

For these reasons, if you are considering patent protection, a patent application should be filed before you make any public disclosures about your invention. NOVA Impact staff can advise you on this, as well as IRIS , for the FCT NOVA community, or the Innovation Unit, for the ITQB community.

Why are patents useful?

Patents are often useful to reduce the risks taken when making major initial investments to bring innovative technologies on the market. As patent owners, Universities may license or sell the rights to the inventions to industrial partners on mutually agreed terms, therefore generating additional revenue streams for their activities, generously shared with the inventors and their research units. It is also a way of maximizing the socio-economic impact of the knowledge produced in the University, by contributing for the generation of new products and processes with industrial application and to more collaborative R&D projects with companies. Moreover, it helps to position the University as an innovative and entrepreneurial institution, creating value to the region and country, as well as to the companies and society at large.

What is the difference between the inventor, the applicant and the owner in a patent?

The inventor is the creator of the invention. In general, for one to be considered an inventor, it is acknowledged that a certain level of “technical creativity” must be met. Inventors are always private individuals and are always entitled to be designated on the patent, regardless of who files the application. Joint inventors or co-inventors exist when a patentable invention is the result of the inventive work of more than one inventor, even if they did not equally contribute in equal parts.

The applicant is the person or entity that applies for a patent, which will not necessarily be the inventor – for instance in Portugal the Universities are typically the owners of the inventions produced within the University – even if the inventor will always keep the moral right to be mentioned as such in the application.

Ownership recognizes a proprietary right to the invention that will in principle vest in the applicant after the patent is granted. As a proprietary property right, the ownership of a patent can be transferred.

The same applies for creators of utility models.

Where is a patent valid?

Patents are territorial rights. In general, the exclusive rights are only applicable in the country or region in which a patent has been filed and granted, in accordance with the law of that country or region.

An invention may, in principle, be freely used by anybody in those countries where it is not protected. This means that a product protected only in Portugal can be produced by somebody else in France, for example. However, you reserve the right to have it imported into Portugal, meaning that import can be prevented or allowed upon payment of a license fee.

Can biological material, including genes, be patented?

The Biotech Directive of the European Union (EU Directive 98/44/EC) defines “biological material” as any material containing genetic information and capable of reproducing itself or being reproduced in a biological system. It covers nucleotide sequences, full length genes, complementary DNA (cDNA), and fragments. Under the Biotech Directive, inventions which are new, involve an inventive step and are susceptible of industrial application are patentable, even if they concern a product consisting of or containing biological material or a process by means of which biological material is produced, processed or used.

Additionally, biological material that is isolated from its natural environment or produced by means of a technical process may be the subject of an invention, even if it previously occurred in nature.

For biological material from the human body, the provisions are slightly different. The simple discovery of the sequence or partial sequence of a gene cannot constitute a patentable invention. Only if any of the following are satisfied can naturally occurring genetic sequences from the human body be patentable:

- biological material isolated or purified from its natural environment;

- biological material produced by means of a technical process (e.g. to identify, purify or classify it, which human beings alone are capable of putting into practice and which nature is incapable of accomplishing, even if it previously occurred in nature) such as artificial DNA constructs, cDNA, genetically engineered proteins;

- discovered to exist in nature and a technical effect is revealed (e.g. gene used in making a certain polypeptide or in gene therapy).

Merely finding and describing a new gene, or identifying the structure of a protein which does not have a clear role or practical use, is not enough to be eligible for patenting.

Can I obtain a patent for a software-related invention?

It depends. Laws and practice in this regard differ from one country or region to another. In some countries or regions, software-related inventions must have a “technical character” to be protected by patent (e.g. Europe), while in other countries such requirements are less stringent (e.g. in general, software can be patented in USA).

In Portugal and Europe, it is not possible to patent the source code of a computer program. We do not have the concept of “software patents” as in the USA; instead at the European level there is the concept of “computer-implemented inventions”, defined as inventions whose implementation involves the use of a computer, a computer network or other programmable apparatus, having one or more features realized by means of a computer program.

It is important to mention that the patentability must not be denied merely because a computer program is involved. As with all inventions, computer-implemented inventions are patentable only if they have technical character, are new, involve an inventive technical contribution to the prior art, and are industrially applicable. The technical effect provided by a computer program can be a reduced memory time access, a better control of a robotic arm, improved user interfaces, etc., meaning that it does not have to be external to the computer (hardware).

Should a patent turn out not to be a viable option for a software-related invention, then using Copyright as a means of protection may be an alternative. Computer programs are generally protected under Copyright as literary works. The protection starts with the creation or fixation of the work, such as software or a webpage. Although, in general, it is not required to register or deposit copies of a work to obtain Copyright protection, in Portugal, software can be registered at IGAC or ASSOFT as Copyright and commercialized through software license agreements. Many companies opt to protect the object code of computer programs by Copyright, while the source code is kept as a trade secret.

B3. Copyright and Related Rights

What are Copyright and Related Rights?

Copyright (Authors’ rights or “Direitos de Autor”, in Portuguese) designate the rights that protect literary or artistic creations, granting the author an exclusive right of economic exploitation, with the power to authorize third parties to enjoy and use the referred creation/work. Copyright also grants the author personal or moral rights, which ensure respect for his/her personal contribution, i.e., the authorship, the authenticity and the integrity of the creation/work. The protection granted by an author’s rights focuses on the expression or manifestation (form) of the creation/work and not on the ideas on which it is based. Ideas and subjects, procedures, systems, operational methods, concepts or discoveries are not protected by Copyright, as these are commands of action or execution without artistic expression.

In the broadest sense, the operation of the Copyright system also includes the rights enjoyed by performers, audiovisual producers and broadcasters, which are often referred to as “Related Rights”. These are not the authors or creators of the works but have a close relationship to them (e.g. they disseminate literary or artistic works, they bring technical and organizational skill to the production of particular expressions of Copyrighted works).

According to the Berne Convention, Copyrighted works include every kind of production in the literary, scientific and artistic domains, such as (non-exhaustive list):

- books, pamphlets and other writings;

- lectures, addresses, and other works of the same nature;

- dramatic or dramatico-musical works and choreographic works

- musical compositions with or without words;

- cinematographic works

- works of drawing, painting, architecture, sculpture, engraving and lithography;

- photographic works;

- works of applied art;

- illustrations, maps, plans, sketches and 3D-works relative to geography, topography, architecture or science;

Although not included in the Berne Convention list, Copyrighted works also include computer programs, defined as a set of instructions that controls the operations of a computer to enable it to perform a specific task, such as the storage and retrieval of information

Learn more at WIPO.

Copyrighted works include every kind of production in the literary, scientific and artistic domains, including computer programs.

How do I represent a proper NOVA Copyright notice?

Although Copyrightable works do not require a Copyright notice, we do recommend that you use one. For works owned by NOVA, use the following notice:

“Copyright ©[year/ano] Universidade NOVA de Lisboa. All rights reserved / Todos os direitos reservados”.

What does open source software mean?

The basic principle underlying Open Source Software is that the software source code is made available, allowing others to modify the software. But this is only one aspect. An Open Source license means license conditions that are compatible with the principles defined by the Open Source Initiative, for instance free redistribution, or no discrimination against persons, groups, or fields of endeavor. For more information see http://www.opensource.org/osd.html.

B4. Trademarks and Designs

What is a Trademark?

A trademark is a distinctive sign which identifies certain goods or services of one enterprise from those of other enterprises or entities/competitors. All graphical representations of a sign can, in principle, be a trademark within the meaning of the law such as words, combinations of letters, logos, three-dimensional forms, slogans, combinations of these elements or even sound trademarks.

A trademark can acquire protection either through registration or through use. It is generally accepted that the sign must be distinctive, and not deceptive or descriptive.

What is an industrial design?

In a legal perspective, an industrial design constitutes the ornamental aspect of a product. An industrial design may consist of three-dimensional features, such as the shape of a product, or two-dimensional features, such as patterns, lines or color.

Industrial designs are applied to a wide variety of products of industry and handicraft items: from packages and containers to furnishing and household goods, from lighting equipment to jewelry, and from electronic devices to textiles.

Registration is the only legal way to protect a design. In Portugal, the registration of a design must be requested to INPI, through the design modality. Product design is the key to consumer choice. Therefore, the appearance of the product can and should be protected. The registration protects a design from being used without the owner’s consent.

To register a design, it must be: (i) not registered yet; (ii) new and unique (cannot be confused with any product, registered or unregistered, that already exists); and (iii) no identical design was made available to the public, in Portugal or abroad, before the date of the application.

Designs which are not entirely new, but which make new combinations of already known elements or different arrangements of already used elements can be registered, giving them a unique appearance.

B5. Trade secrets and Research Materials

What is a Trade Secret?

A Trade Secret is information which is not publicly known (a formula, manufacturing process, method of doing business, or technical know-how), that is kept confidential so that it gives its holder a competitive advantage. Unlike a patent, a trade secret does not confer exclusive rights on its holder, i.e., if someone develops the same information, they can use it freely. However, the unauthorized acquisition, use or disclosure of such secret information in a manner contrary to honest commercial practices by others is often regarded as a violation of the trade secret protection and it is considered an illegal act, subject to fining.

In general, to qualify as a trade secret, the information must be:

- commercially valuable because it is secret;

- be known only to a limited group of persons, and

- be subject to reasonable steps taken by the rightful holder of the information to keep it secret, including the use of confidentiality agreements for business partners and employees.

What are Research Materials?

According to NOVA’s IP Policy, Research Materials include:

- Biological materials, including DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid);

- Other non-biological materials or products;

- Engineering projects;

- Database Content;

- Prototypes;

- Associated research equipment and data;

- Other elements associated with the previous points.

Please note that scientific collaboration that involves transferring research materials from NOVA to other entities, and from these to NOVA, must be agreed in writing through an MTA (cf. E6) and approved by the Rectorate or by the Organic Units, when they have specialized services, upon presentation of a reasoned request.

Where can I file biological material?

Under WIPO’s Budapest Treaty, people seeking patent protection for biological material are required to deposit a sample of it with an international depositary authority where it is tested (for viability) and stored for up to 30 years.

Are you looking for a recognized international depositary authority for biological material? The following link lists all recognized depositary authorities: Budapest Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure.

C. Intelectual Property Policy of NOVA

This section focuses on the Intellectual Property Policy in force at NOVA, aiming to complement the formal IP Policy document with some examples and additional explanations for specific cases that might help you to better understand the underlying principles of such Regulation.

C1. General Considerations

Is there any IP regulation at NOVA? Why and what for?

Yes. NOVA’s Intellectual Property Policy is regulated by Regulation Nº 1104/2020, published in Diário da República on 22nd of December, 2020. If you work, study, research or collaborate with NOVA, you should read it carefully.

The creation and dissemination of knowledge is at the heart of every university activity. The challenge is realizing how this knowledge can best be utilized as an asset that can provide the maximum value to the economy, society and the university itself. Beyond the potential to generate income, NOVA has the responsibility to protect its IP rights in the best way that it can and to ensure that society can benefit from the funding that is given to the University.

Therefore, it is crucial to practice an adequate and efficient management of NOVA’s intellectual property, following the best international practices. Internal and external agents should clearly know on what to count when it comes to IP rights (industrial property and Copyright). On one hand, for the knowledge to be transferred to the marketplace, the stakeholders need to feel confident and ensure that the ownership of IP rights is fully and properly regulated; on the other hand, researchers will be much prone to develop inventions or to create other forms of socio-economic impact if they have the proper incentives to follow that path.

NOVA recently revised its IP Policy based on principles of transparency, equity, sustainability and efficiency to carry out the corresponding knowledge transfer process.

The present Regulation clearly identifies who is covered by its provisions, it identifies NOVA’s ownership over the IP rights within the University and establish the main duties of inventors, creators or authors. Moreover, it regulates the decision process, the forms of protection and exploitation of IP rights (creating the conditions to pursue the most adequate path for maximizing the socioeconomic valuation of the invention), as well as the sharing of revenues resulting from the commercialization of IP rights, among other provisions necessary for the effective regulation of this matter, with the ultimate goal to create the conditions to maximize the socio-economic impact of the knowledge produced at the University .

How do I know if NOVA’s Intellectual Property Regulation applies to me?

Individuals to whom NOVA’s Intellectual Property Policy applies are defined in article 4 of the IP Policy.

The IP Policy applies to NOVA faculty, researchers, students, employees/staff and research fellows, and to research visitors or other individuals collaborating with NOVA, its Organic Units and associated Research Units, using significant NOVA resources (funds, infrastructures, equipment, lab materials, etc.). If you have any doubt, please contact NOVA Impact. If you are related to FCT NOVA, you should contact directly IRIS, and if your related to ITQB NOVA, you should contact the ITQB’s Innovation Unit.

What are considered NOVA’s resources?

NOVA’s resources are defined in article 3 of the NOVA’s IP Policy.

Significant use of NOVA’s resources means the use which has been relevant for conceiving or developing the invention, creation or work. It includes, for example, the use of specialized, research-related facilities, equipment or supplies, libraries and intellectual property owned by NOVA, regardless of whether or not is protected by IP rights.

I think I have created or invented something, what should I do?

You may contact the NOVA Impact office to have a preliminary talk on the results to be disclosed. If you are related to FCT NOVA, you should start by contacting IRIS, and if you are related to ITQB, you should contact the ITQB’s Innovation Unit.

C2. Ownership

In which situations does the ownership of an IP right belong to NOVA?

In the light of what is defined in the Portuguese Industrial Property Code (art. 59º), approved by Decree-Law 110/2018 of December 10, NOVA holds ownership of all industrial property rights (as well as trade secrets), of inventions, materials or other industrial creations developed by NOVA faculty, researchers, students, staff, visitors or other individuals collaborating with NOVA, that use resources from NOVA, as defined in the previous sub-section. In the case of individuals who have a professional exclusive relationship with NOVA, this applies regardless of the use of NOVA resources.

The participation of individuals not affiliated to NOVA, in unpaid research activities, involving the use of NOVA resources is dependent on their acceptance of this IP Policy and the assumption of the obligation to transfer to NOVA any industrial property rights or trade secrets arising from the use of these resources, through a declaration subscribed by them.

In regard to Author’s Rights (including software protected by Copyright), by default, the authors hold the rights over literary, scientific or artistic works conceived or developed within the scope of any research or teaching activity carried out at the University, unless i) the work results from the execution of a contract with the University, or Organic Unit, which provides for a different regime (e.g. “obra por encomenda”) or ii) the work implied a significant use of resources or financial provisions from the University/Organic Unit – in this case, the ownership of Copyright should be defined, with good reason, by the Rector based on the spirit of the NOVA’s IP Policy.

In any case, the inventor(s)/creator(s) keep the right to be mentioned as such in the applications submitted by NOVA, and the authors keep their moral rights, as predicted in Portuguese legislation.

For detailed information, check the Part II of the IP Policy, namely article 5 for industrial property rights ownership, article 7 for Copyright ownership and article 8 for computer-implemented inventions and computer programs ownership.

I am a Ph.D./MSc. student doing my thesis/dissertation: how is IP regulated?

The Copyright over the thesis/dissertation belongs to the student (nr. 1 of article 7 of the IP Policy).

However, the results produced during the development of a Ph.D. thesis or MSc. dissertation may have originated or may originate a patent or trade secret owned by NOVA – for example, if the student is remunerated (even if through a scholarship from FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia) and have used significant resources from NOVA. In these cases, students must comply with the duties as defined in article 9 of the IP Policy (e.g. confidentiality or not disclosing the invention before being authorized to do so).

In case of doubt, you should contact your supervisor and/or the NOVA Impact team and/or IRIS if you are a FCT NOVA student, or the Innovation Unit if you are a student from ITQB.

If NOVA decides not to protect an invention or creation, may I pursue with the protection process on my own?

Once the invention is disclosed, NOVA will decide whether to protect it or not (by patent application or trade secret) based on the potential commercial potential of the invention.

If NOVA decides not to take ownership of a certain IP right (Copyright included, when applicable), the inventor(s)/author(s) will acquire the full rights related to the respective invention, creation or work, including the rights of exploitation, and may request, in their name and at their own expenses, the adequate legal protection (see number 6 of article 12 of the IP Policy). In these cases, NOVA is entitled to receive a compensation if and when the commercialization succeeds, reflecting its contribution to the invention, creation or work, to be agreed in writing.

C3. Responsibilities

Who is responsible for NOVA’s Intellectual Property?

The Rector decides on every matter related to NOVA’s intellectual Property Rights.

The Rector is supported by a member of the Rectoral team who coordinates the areas of Social and Economic Value Creation, supervises the NOVA Impact structure and is, by default, the President of the Value Creation Council.

The Value Creation Council (VCC) is an advisory body to the Rector on issues related to the University’s Third Mission. Its mission is to promote reflection and contribute to define strategic orientations towards a policy of socio-economic valorisation of knowledge and a closer relationship with companies and society at large, including the definition of best practices to manage and value the University IP rights. VCC is formed by representatives of all Organic Units of NOVA recognized by their expertise in these areas, hence guaranteeing that all Schools are represented and can have an active voice in the definition of the best procedures and strategies.

For example, the VCC is entitled to issue an opinion on the decision process, as defined in the numbers 2 and 5 of articles 12 and 15 of the IP Policy, respectively.

NOVA Impact is the knowledge transfer support arm of NOVA’s Rectorate, with a vision to create an impactful innovation ecosystem with NOVA University at its heart. The NOVA Impact team works with academics, researchers and students to apply and maximize the impact of their expertise and research outputs, to foster knowledge transfer and transform innovative results into social and economic value.

NOVA Impact works also in straight collaboration with the different Organic Units, supporting the professional management of IP rights (from identification to protection and valorisation). FCT NOVA and ITQB also have professional offices to support their research community in the areas of knowledge transfer and IP, which may be the first contact point in the respective Schools, following the general procedures defined by the Rectorate to protect and exploit IP rights.

Who is responsible for defining the best route to protect and commercially explore an invention or creation at NOVA?

NOVA, through its specialized services on intellectual property and tech transfer, is responsible to define the best approach for protection and commercial exploitation of an IP right. Nevertheless, the support and cooperation of the inventor/author is considered critical to the success of these processes.

NOVA Impact, or the specialized support services of FCT NOVA (IRIS) or ITQB (Innovation Unit), in articulation with the Rectorate, will manage and conduct the necessary steps to protect and explore IP rights owned by NOVA. Activities of this specialized services include researching the market for the technology, identifying third parties to commercialize it, entering into discussions with potential licensees, negotiating agreements, monitoring progress, among other relevant tasks.

For certain inventions, the decision may pass to not apply for a patent if the economic valuation of the research results is expected to be maximized following a trade secret route.

The most appropriate approach to commercialization depends largely in the stage of development of the technology. Many inventions need further development or validation prior to commercial licensing, which can occur through industry collaborations.

Regarding IPR co-owned by other entities, who makes the decisions about protection and commercialization strategies?

All collaborations that may imply inventive activity must be preceded by an agreement celebrated between the parties, regulating the intellectual property, as defined in article 13 of the NOVA’s IP Policy.

All agreements must include clauses regulating:

- The ownership of the Background and Foreground IP;

- The assumption of the costs associated with the process of preparation, maintenance, protection, promotion and commercialization of the IP rights with commercial potential;

- The benefits that may be assigned to NOVA, in cases where NOVA may not be considered as owner of the IP rights;

- Confidentiality issues, publication, and dissemination of research results.

Generally, if the other institution is a University or Research Institution, there will be an agreement defining who will take the lead in protecting and licensing the technology, sharing expenses associated with the patenting process and allocating any licensing revenues.

Whenever applicable, who is responsible to collect the declarations of students or research visitors assigning rights to NOVA?

According to the IP Policy, if an individual, who is unpaid to perform research activities or do not have an employment relationship with the University (e.g. MSc. students and visiting researchers), collaborates with NOVA and invents or creates something, using significant resources from NOVA under its research activities, she/he must assign their rights to NOVA.

The responsible person of each Research Unit (or Organic Unit) with whom these individuals collaborate is responsible to collect the respective declarations assigning the IP rights to NOVA.

It is therefore essential that all individuals participating in the research be made aware of their obligation to assign rights to NOVA and collaborate in the IP protection and commercialization processes, as needed. In the case of visiting researchers from external institutions an agreement must be previously drawn up between the two entities, regulating the terms of IP rights that may arise from his/her research activities, including Background and Foreground IP.

Doctoral students with a scholarship from FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, for example, are considered to be paid for their research activities and, by default, NOVA owns the industrial property rights arising from their work within the University (article 5 of the IP Policy).

D. Agreements

What types of agreements and considerations apply to technology transfer?

The primary types of agreements negotiated by NOVA specialized services in IP and KT include the following:

- Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs), also known as Confidential Disclosure Agreements (CDAs), are often used to protect the confidentiality of an invention, technology or pre-publication information, and are typically used in the process of research commercialization.

- Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs) are used for incoming and outgoing materials (including biological materials) at NOVA and are administered by NOVA specialized services. These agreements describe the terms under which NOVA researchers may exchange materials with other academic, government or commercial organizations, typically for research or evaluation purposes. MTAs offer important protections regarding such issues as ownership, the ability to publish, and rights to resulting inventions. Intellectual property rights can be endangered if materials are used without a proper MTA.

- IP Sharing Agreements (or Inter-Institutional Agreements) describe the terms under which two or more entities (Universities, companies, etc.) will collaborate to share financial, administrative, marketing, and other responsibilities of managing jointly owned Intellectual Property.

- Industry Research Collaboration Agreements describe the terms under which the University typically collaborates with a company in a research project, both providing intellectual contributions to the project outcomes, and where the new solutions created with contributions from both parties are jointly owned by them. All Background IP shall remain the sole and exclusive property of the party owning it, and specific access rights to the Background IP may be negotiated for the purpose of the project to the other party, if needed to perform a certain project task.

- Licensing Agreements defined as contracts between two parties (the licensor and licensee) in which the licensor grants the licensee the right to use the IP right (trademark, logo, patented technology, know-how) to produce and sell goods owned by the licensor. While the sale of a right (transmission) over a patent, for example, implies the transfer of ownership, the licensing process allows the owner to retain its position as such, granting the licensee to use the right over the patent for a certain period of time and under agreed conditions.

- Contract Research Agreements may be used where a company will pay a full commercial fee for specified research to be performed using university facilities, and company expects to own all the IP arising from the research. The overheads charged for this type of agreement are often higher, compared to collaborative research agreements.

- Industry-Sponsored Research Agreements describe the terms under which sponsors provide research support (financial or in-kind) to research groups from NOVA to undertake a certain research project. These agreements should protect researchers’ scholarly independence and right to freely publish their results, and may include Option clauses.

- Option Agreements, or Option Clauses within research agreements, describe the conditions under which NOVA preserves the opportunity for a third party to negotiate a license for intellectual property.

Sample and template agreements are available upon request to NOVA Impact.

E. Disclosure, Assessment, Protection and Commercialization of IPR

This section aims to explain the main procedures applied at NOVA, from the disclosure process to the commercialization stage of a certain IPR owned by the University.

E1. Invention or Copyright Disclosures

What is an Invention or Copyright Disclosure?

An Invention/Copyright Disclosure is a description of your invention or copyrightable material (including software) that must be provided to the University’s specialized services. The Disclosure should include all information needed to begin pursuing protection and valorisation activities, including all contributors to the ideas or research outputs (students, faculty, researchers, etc.), even if they are not affiliated to NOVA. It is very important that you note the date of any upcoming publication or other public disclosure describing the IP asset. This document will be treated as confidential. After submission of the Invention or Copyright Disclosure Form you should be shortly contacted by the assigned knowledge transfer officer to discuss the next steps, which may include literature search to review the novelty of the research results, protectability, marketability, among other issues.

Is it mandatory to disclose an invention or creation?

Yes. Following the Portuguese Industrial Property Code (art. 59º), NOVA’s IP Regulation determines that any invention/creation must be disclosed by the inventors to the University. At NOVA we defined a maximum period of 3 months for invention disclosure since it is considered concluded. This applies whenever you realize you may have discovered something with potential commercial value.

In case there are two or more inventors/creators from NOVA, you should appoint a representative to be the point of contact with NOVA’s specialized services, as defined in the article 9 of the IP Policy.

What is the procedure at NOVA to disclose an invention or Copyrightable material?

You should fill the appropriate disclosure form available here and send it to the NOVA Impact office, or to IRIS if you are affiliated to FCT NOVA, or to the ITQB’s Innovation Unit if you are affiliated to ITQB.

A skilled employee of these services will begin the process of evaluating the invention for patentability, commercial potential, and contractual obligations. The first step will typically be a meeting with the inventor(s)/author(s), who may be also requested to participate in a literature search of prior art, if applicable.

Direct contacts of specialized services: NOVA Impact (novaimpact@unl.pt); FCT NOVA / IRIS (gab.ad.iris@fct.unl.pt); ITQB (marta.ribeiro@itqb.unl.pt).

E2. Protection

What should I do if I think I do have an idea or invention worth protecting?

You should contact the NOVA Impact office. If you are related to FCT NOVA you should start by contacting IRIS, and if you are related to ITQB you should contact the ITQB’s Innovation Unit.

How is the patent protection route defined? Is international protection admissible?

The potential economic value of an IP right may be substantially increased if an extension beyond the Portuguese territory is sought. However, international patent application and maintenance is quite costly (can reach thousands of euros in a few years). For that reason, international application is often dependent on the viability of the invention commercialization, demonstrated for example by the existence of a commercial partner that can support the associated costs (as defined in the number 4 of article 15 of the IP Policy).

In some cases, even if a commercial partner is not yet identified, the decision may pass to legally protect the invention abroad or to maintain an international patent application, considering that commercialization opportunities are promising, and depending on the extent of the funds available for investing in foreign patents.

How is a patent application prepared? Does NOVA help in the preparation and protection of patents?

Writing a robust patent application requires extensive expertise (ideally legal and scientific expertise). A poorly written patent application may compromise the success of the invention commercialization.

Questions like “Is it better to patent the finished product, a part of it or the method for manufacturing the product – or all three?” or “In which countries should the patent be protected?” should be thoroughly analyzed. A skilled person must be able to understand the solution. It must also be clear what precisely you are claiming protection for.

At NOVA we have been dealing with external partners (patent attorneys) specialized in drafting patents in different fields of technology and respond to patent offices in the countries in which patents are filed. These processes often involve significant expenses and are managed by NOVA’s specialized services.

NOVA is responsible to ensure that a patent application has enough quality to be filed, in order to safeguard the University interests. All inventors from NOVA must collaborate in this process, providing all the information and documentation as needed. This is a very important aspect, as no internal service knows more about the invention or creation than the inventors themselves.

PATENTING YOUR INVENTION

This figure illustrates a typical process at NOVA, from the invention disclosure form to the filing an international patent application. Note that this process may be different in certain situations, as the best protection approach is defined on a case-by-case basis, considering the maximization of the socio-economic impact of each invention.

What should I do to register a trademark or design under my activities at NOVA?

You should contact NOVA Impact. If you are related to FCT NOVA you should contact IRIS, and if you are related to ITQB you should contact ITQB’s Innovation Unit.

E3. Marketing and Commercialization

IP Rights – What can be licensed/commercialized?

- Patents (e.g. the method of production);

- Copyright (e.g. software);

- Database rights (e.g. customer details);

- Design rights (e.g. the shape and appearance of a bottle);

- Knowledge (know-how, such as recipes, formulations under trade secret);

- Research reagents and materials (e.g. model organisms, proteins, DNA/RNA, etc.);

- Trademarks (e.g. logo and other distinctive signs).

How does NOVA market its Intellectual Property Rights?

From existing relationships of the inventors/authors and technology transfer staff, to market research analysis, showcase of the technologies and advanced expertise in national and internationals events or online matchmaking platforms, several strategies and sources can be used to identify potential licensees and market inventions, or other developments owned by NOVA.

At NOVA we have been showcasing our most promising technologies in the international platform IN-PART, as well as in the NOVA Impact website. In particular cases, we have also been collaborating with external IP brokers to help us in this challenging process.

What are the different payment types of a research commercialization/licensing agreement?

An agreement may include multiple types of payments. The categories mentioned below are not exhaustive and some of them can be combined in the same agreement:

- Single lump sum payment – a single payment for a determined period of time, typical of agreements in which the technology offers a relatively low industrial and commercial risk.

- Royalties – based on a percentage of the price of the licensed product, or on a percentage of the product sales operational results. This type of payment shares the risk between the licensor and the licensee, since the licensor receives a larger or a smaller payment depending on the sales success.

- Fixed fee payment – a fixed payment per sold unit or technology utilization may be established.

- Up-front payment – a payment required by the licensor on or shortly after the signing of a license agreement, whose purpose is to assure the licensee commitment in the invention industrialization and commercial success.

- Minimum cash payment – annual payments required by the licensor for the licensee to maintain its exploitation rights. The aim is also to assure that due diligence is being taken by the licensee in the invention commercialization success.

- Milestone payments – payments required to the licensee each time certain development or commercialization objectives or milestones are successfully attained such as, the conclusion of an R&D stage, the beginning of sales or the development of a new application based on the technology.

- Option agreements and options payments – an option the right to make future decisions relative to the acquisition or exploitation of a technology. Option agreements generally last for less than 1 year and are very useful on the creation of new enterprises.

- Sub-licensing payments – if the licensee is interested in distributing the technology to third parties, the contract must preview how the gains will be distributed among licensors, licensees and sub-licensees (common in exclusive licensing agreements).

- Equity payments – some universities opt for an equity participation in a spin-off, assuring financial support for the firm or tech transfer without or at reduced cost for the firm. So far, NOVA does not take equity on its recognized spin-offs but provides them several benefits, such as license in exclusive terms the IP generated by the spin-off promoters, without fees until the commercialization stage.

How long does the commercialization process take?

To find a potential licensee for a technology can take months or even years, depending on its attractiveness and development stage, competing technologies, and the amount of work required to increase the maturity level of the technology. Early-stage technologies typically require substantial efforts to attract a licensee.

Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) are a type of measurement system used to assess the maturity level of a particular technology. Technologies rated at a TRL level of 7 or higher are easier to license. Because university technologies are often too early-stage to attract industry investment, NOVA, in partnership with inventors, strives to increase the TRL rating, increasing the chances of successful licensing.

I have found a potential licensee - what should I do?

You should contact NOVA’s specialized services on IP commercialization. Generally, the most successful research commercialization results are obtained when the inventor or author and the licensing professionals work together as a team to market and promote the use of the IP asset.

Your network of contacts can be extremely useful as research relationships are often a valuable source for licensees, but do not start any negotiation process without involving NOVA’s specialized services.

What should I do to commercialize a software I have developed at NOVA?

The disclosure process must be followed.

Computer programs in which NOVA acquire rights may be either copyrighted or patented (if considered “computer-implemented inventions”) and made available by NOVA for commercial purposes, under various forms of Copyright licenses or patents (if applicable). Potential revenues will be shared according to what is mentioned in section E4. If authors desire to distribute software for noncommercial research purposes which has been commercially licensed by NOVA to third parties, such licensing must be validated by NOVA.

E4. Revenue Sharing

What is the revenue share assigned to inventors, creators, or authors?

With the revision of NOVA’s IP Policy, you know exactly the percentage of revenues assigned to NOVA’s inventors, creators or authors. In addition to these, the recipients of the net revenues are also the Organic Unit(s) to which they belong, the respective Research Group or Research Unit, and the Rectory.

The benefits to be distributed among these recipients (net revenues) correspond to the amounts after fees and taxes, including the costs incurred with the protection and maintenance of the correspondent IP rights, consultancy and commercial exploitation of the results.

Inventors, creators or authors get 50% of the net revenues! In many Universities, in Portugal and abroad, the percentage attributed to inventors decreases as revenues increase. At NOVA, you know exactly on what to count from the very beginning and at any case. This share will be divided equally among all inventors, creators or authors unless all them agree in writing to a different distribution.

In addition, 20% of the revenues can be allocated to the Research Groups/Units of the inventors, creators or authors, to compensate their units for creating the conditions to develop commercially valuable IP rights and to be reinvested in R&D and innovation activities. Note that this percentage is mobile in the sense that it be allocated to those who cover the costs of protecting and maintaining the IP rights within NOVA, for example the Rectory or the Organic Unit. Therefore, it is very important that researchers consider this type of costs when applying to funded projects that may involve inventive steps (check article 15 of the IP Policy), so that their research groups take full advantage of the revenue distribution.

The remaining 30% are shared between the Organic Unit (20%) to which the inventor(s) belong and the Rectorate (10%) to be used, by policy, for supporting and investing in tech transfer activities, and in the case of Organic Units also for research and innovation activities. If specialized support for the protection of IP rights is provided by the Organic Unit own service, this part of the benefits’ sharing will be 25% for the Organic Unit and 5% for the Rectorate.

As an inventor, if you want, you can transfer to your Organic Unit, Research Unit or the Rectory all or part of the revenues assigned to you.

Please note that if the IP rights are co-owned with other institutions/entities (e.g. NOVA and other University), first the revenues are shared between the co-owners and only then within NOVA according to the described revenue sharing scheme.

For additional information, check article 18 of NOVA’s IP Policy.

How do I receive the revenues resulting from the commercialization of an IP right? Are taxes applied?

Revenues are considered as income related to IPR and not as supplements to the salary. These revenues are compatible with exclusivity requirements.